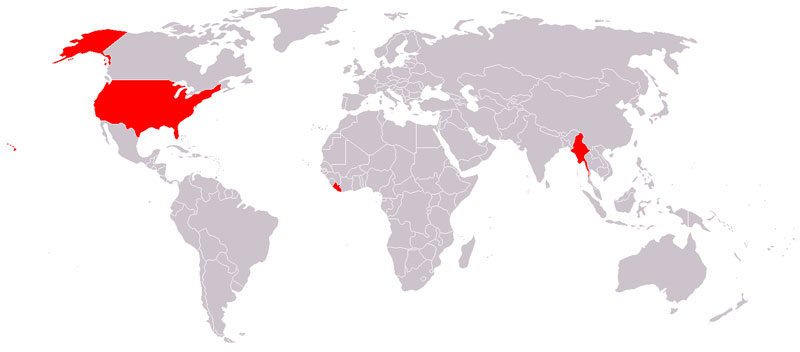

Liberia, Myanmar, and the United States are the only countries that don't use the metric system

As Vox’s Susannah Locke wrote, "The measuring system that the United States uses right now isn’t really a system at all. It’s a hodgepodge of various units that often seem to have no logical relationship to one another — units collected throughout our history here and there, bit by bit. Twelve inches in a foot, three feet in a yard, 1,760 yards in a mile." That’s why the rest of the world uses the metric system, where "all you need to do is multiply or divide by some factor of ten. 10 millimeters in a centimeter, 100 centimeters in a meter, 1,000 meters in a kilometer. Water freezes at 0°C and boils at 100°C."

But, as some people still remember (hello, Michel T!), there was a movement in the 70ies to move to the metric system in the US as well. This is documented in the recent book "Whatever happened to the metric system?" reviewed by the New York Times hereunder

WHATEVER HAPPENED TO THE METRIC SYSTEM?

How America Kept Its Feet

By John Bemelmans Marciano

Illustrated. 310 pp. Bloomsbury. $26.

In the 1970s, children across America were learning the metric system at school, gas stations were charging by the liter, freeway signs in some states gave distances in kilometers, and American metrication seemed all but inevitable. But Dean Krakel, director of the National Cowboy Hall of Fame in Oklahoma, saw things differently: “Metric is definitely Communist,” he solemnly said. “One monetary system, one language, one weight and measurement system, one world — all Communist.” Bob Greene, syndicated columnist and founder of the WAM! (We Ain’t Metric) organization, agreed. It was all an Arab plot “with some Frenchies and Limeys thrown in,” he wrote.

Krakel and Greene might sound to us like forerunners of the Tea Party, but in the 1970s meter-bashing was not limited to right-wing conservatives. Stewart Brand, publisher of the Whole Earth Catalog, advised that the proper response to the meter was to “bitch, boycott and foment,” and New York’s cultural elite danced at the anti-metric “Foot Ball.” Assailed from both right and left, the United States Metric Board gave up the fight and died a quiet death in 1982.

In his entertaining and enormously informative new book, “Whatever Happened to the Metric System?,” John Bemelmans Marciano tells the story of the rise and fall of metric America. With a keen ear for anecdotes and a sharp eye for human motivations, Marciano brings to life the fight over the meter, its champions and its enemies. The 1970s bookend his narrative, but the reader soon finds the struggle lasted not a decade but centuries. And in what was to me the book’s greatest revelation, the meter — that alleged vehicle of international Communism — turns out to be American through and through.

The father of American metrication was none other than Thomas Jefferson, who in the 1780s turned his attention to replacing the menagerie of doubloons, pistoles and Spanish dollars then in use in the states. Jefferson proposed minting a new dollar, but whereas the European coins were divided into halves, eighths, sixteenths, etc., the American coin would be divided into tenths, hundredths and thousandths. When Jefferson’s plan was approved by Congress, the United States became the first country to adopt the decimal system for its currency.

That money is related to measurement might seem counterintuitive today. But as Marciano points out, until very recently the value of coins was ultimately dependent on their weight in gold or silver, which means the divisions of a currency imply a division of weight. And so, when Jefferson arrived in Paris as a diplomat in 1784, he joined forces with French luminaries in promoting a complete reform of weights and measures. Their opportunity came only a few years later, when at the height of the French Revolution its leaders cast away all traditional measures and replaced them with the new meter, kilogram and liter. Jefferson, who had returned home in 1789, was convinced the new system would be promptly adopted in America.

It didn’t turn out that way. As France descended into terror and war, the metric system became entangled in a worldwide struggle over its legacy. To its supporters it stood for reason and democracy; to its detractors, godlessness and the guillotine. It was not until the aftermath of World War II, when new global institutions were established and a host of new nations adopted the meter, that its place as the near-universal measure was secured.

In America, however, repeated efforts at metrication, from Jefferson to Jimmy Carter, were scuttled by a formidable combination of hostility and indifference. According to Marciano the debate is now over, since the digital revolution has made conversion instantaneous and a change of system pointless. Still, as his book beautifully shows, clashes over the meter were more often about ideology, not utility. And so, as long as the struggle continues over reason and faith, universalism and tradition, I wouldn’t count the meter out.

No comments:

Post a Comment